Urban geographer and gender expert, prof. Brigitte Wotha, Ostfalia University of Applied Sciences, photo (c) Brigitte Wotha

“Everything is about learning. You too can learn gender mainstreaming practice. Your district’s officers should get training in gender mainstreaming, gender training and projects that embody these principles.’’

Brigitte Wotha, professor, urban geographer, Ostfalia University of Applied Sciences

Interview by Milota Sidorova, edits: Michael Higgs

Why have you become interested in gender?

I was always interested in the differences in how men and women were treated. When I was a child my uncle was a pilot of large ships. I wanted to become a pilot, too. But my uncle told me: no, you can’t become a pilot, because they don’t choose women. I thought that was unfair.

At the university I was doing a lot of equality work, when my students came and told me to teach equality. I started my first class on gender equality at the time when gender planning meant women-sensitive planning. We started with a class exploring cities from a woman’s view and to try and make cities fairer for women. This was just the beginning.

Many people understand gender as the issues of women.

Gender is more radical than women’s issues. Women’s issues frame the world of inequalities where these are always victimised women talking. Gender target everyone. If you promote equality you have to include men too. To achieve an equilibrium, it means taking something from men and that hurts them. We have to talk about the entirety.

Do you think that people find the term ‘gender’ more palatable than ‘feminism’?

Feminism is a bad f*** word and it keeps getting worse. People get organised against feminism even here in Germany. Gender is more difficult to understand. If you talk to people outside the English speaking community, they will not understand the word. But I still use it to start the discussion about equality.

How would you then take Eva Kail’s work in Vienna, where she started an office on women’s needs in the city?

At that we needed to put the focus on women’s needs. Nobody acknowledged the needs of women. They were thinking about women as being weak and in need of help, but nowadays the knowledge and institutions focused on gender equality have increased, we’ve received resources and we’ve conducted research on women’s needs - we are strong enough to talk about distributions between genders. Women’s issues do not hurt men. Gender hurts them because it means they have to share resources, money and power - this is far more radical than receiving support out of a position of someone in need of help.

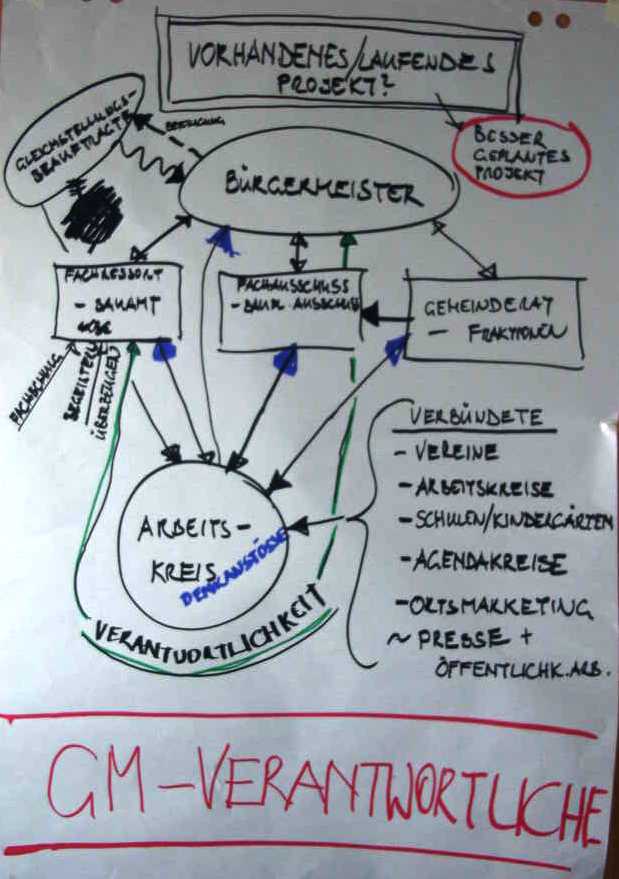

Professor Wotha with her students visiting Prague 7 City Hall and discussing aspects of informality in urban planning, photo (c) Milota Sidorova

Germany adopted gender mainstreaming earlier than Austria.

We did it in a different way and started with gender mainstreaming at a structural level where one must change the institutions. Mainstreaming is focused on balancing institutions, not on specific projects. In Vienna, Eva Kail started with projects that evolved into policies. It made women’s rights visible. We always look into projects in Vienna and Vienna looks to us at a structural level.

But generally, you cannot say gender equality is distributed equally all over Germany, because it still depends on the assertiveness and commitment of individuals. We are still missing these structural changes in German society. Still, it has become easier over the past few years. In the public administration of Germany, we have a hierarchical and objective-oriented administration system. Gender mainstreaming as a top-down strategy came from the European Union in 1990s. In some cities the councils decided on gender mainstreaming and then it had to be adopted by the public authorities.

How did the administration change?

Suddenly people were asked what they did to support gender mainstreaming. Sometimes the answer was nothing and then it stopped. Sometimes they stated success in projects. As it became part of mandatory reporting in the administration, people started to think about gender mainstreaming in a more natural sense.

Were quotas part of the measures?

We discussed a lot on that, especially in the public sector. Here they worked well. Outside the public sector, we still have to get more women into those higher positions.

What was the effect of having more women in the public administration of the city?

It is not that easy. You can’t expect that processes will change only because you have more women in them. In the beginning, it was always one woman between men, you know that situation yourself. Usually, these ‘lonely riders’ got all the agenda with social politics, gender mainstreaming and sometimes with sustainability, too – poor women. Often those women were overworked or thematically overloaded and said: stop, I need more resources to achieve this agenda.

One of participatory projects of proff. Wotha focused on the youth, photo (c) archives, Brigitte Wotha

Gender mainstreaming measures have seen cuts in Germany or as a topic it may not even appear as an objective for European Commission in the next period. Have we solved gender?

Before it became objective, we were still carrying out research and other activities from our own money. Many things have been improved in Europe due to gender mainstreaming. I am positive they won’t cut it completely. There will always be cuts and attacks on gender-related budgets and we have to be aware of it. That is why we need to have our networks and lobbying. We started fighting in 1990s and today we are still fighting - but there are many more of us than 30 years ago.

How do you teach gender in your classes?

In our university, students must study at least one class in gender mainstreaming, diversity management and business ethics. I discuss with them stereotypes in their study topics like economics, marketing and urban planning. I teach them methods to deconstruct narratives of stereotypes and give them instruments for planning. Gender checks for example. I work with them through practical examples – for example, how do you design a kindergarten or museum on gender mainstreaming principles?

What have you learned about Prague 7 urban planning and its ability to serve all people?

I know a little about the concepts of fairness in the city, so I don’t know. But from what I have seen I think the city seems to be too weak when negotiating with investors. Prague 7 is a very precious and growing part of Prague. Politicians always say, ‘we have dealt with the investors’ and then they say, ‘we can’t change anything’. I think more courage would suit them. We met the newly-elected politicians: I hope they won’t change when they get to the city council. The danger is that they may lose their contact with the local community.

Thank you!